A newly opened museum in India houses the remains of American planes that crashed in the Himalayas during World War Two. The BBC’s Soutik Biswas recounts an audaciously risky aerial operation that took place when the global war arrived in India.

Since 2009, Indian and American teams have scoured the mountains in India’s north-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, looking for the wreckage and remains of lost crews of hundreds of planes that crashed here over 80 years ago.

Some 600 American transport planes are estimated to have crashed in the remote region, killing at least 1,500 airmen and passengers during a remarkable and often-forgotten 42-month-long World War Two military operation in India. Among the casualties were American and Chinese pilots, radio operators and soldiers.

The operation sustained a vital air transport route from the Indian states of Assam and Bengal to support Chinese forces in Kunming and Chungking (now called Chongqing).

The war between Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Japan) and the Allies (France, Great Britain, the US, the Soviet Union, China) had reached the north-eastern part of British-ruled India. The air corridor became a lifeline following the Japanese advance to India’s borders, which effectively closed the land route to China through northern Myanmar (then known as Burma).

The US military operation, initiated in April 1942, successfully transported 650,000 tonnes of war supplies across the route – an achievement that significantly bolstered the Allied victory.

Pilots dubbed the perilous flight route “The Hump”, a nod to the treacherous heights of the eastern Himalayas, primarily in today’s Arunachal Pradesh, that they had to navigate.

Over the past 14 years Indo-American teams comprising mountaineers, students, medics, forensic archaeologists and rescue experts have ploughed through dense tropical jungles and scaled altitudes reaching 15,000ft (4,572m) in Arunachal Pradesh, bordering Myanmar and China. They have included members of the US Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), the US agency that deals with soldiers missing in action.

With help from local tribespeople their month-long expeditions have reached crash sites, locating at least 20 planes and the remains of several missing-in-action airmen.

It is a challenging job – a six-day trek, preceded by a two-day road journey, led to the discovery of a single crash site. One mission was stranded in the mountains for three weeks after it was hit by a freak snowstorm.

“From flat alluvial plains to the mountains, it’s a challenging terrain. Weather can be an issue and we have usually only the late fall and early winter to work in,” says William Belcher, a forensic anthropologist involved in the expeditions.

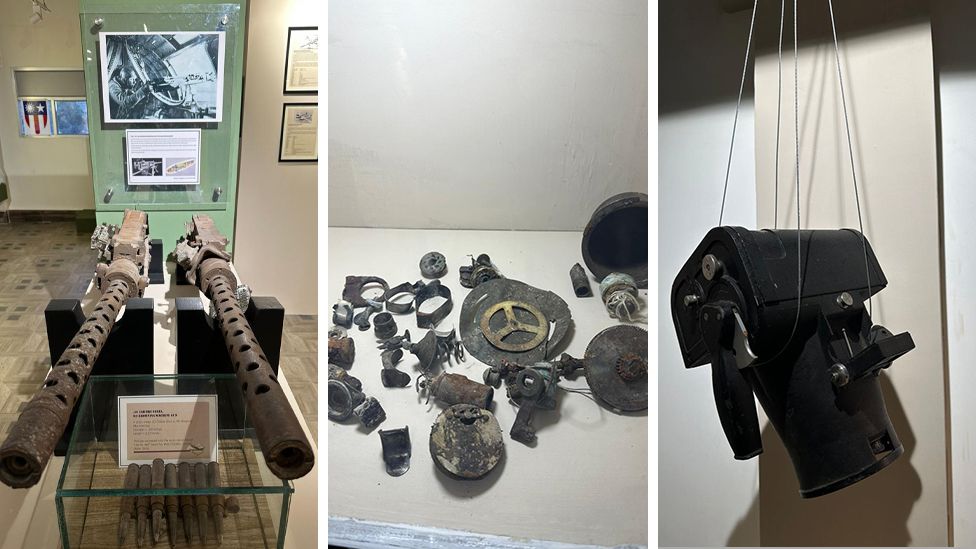

Discoveries abound: oxygen tanks, machine guns, fuselage sections. Skulls, bones, shoes and watches have been found in the debris and DNA samples taken to identify the dead. A missing airman’s initialled bracelet, a poignant relic, exchanged hands from a villager who recovered it in the wreckage. Some crash sites have been scavenged by local villagers over the years and the aluminium remains sold as scrap.

These and other artefacts and narratives related to these doomed planes now have a home in the newly opened The Hump Museum in Pasighat, a scenic town in Arunachal Pradesh nestled in the foothills of the Himalayas.

US Ambassador to India, Eric Garcetti, inaugurated the collection on 29 November, saying, “This is not just a gift to Arunachal Pradesh or the impacted families, but a gift to India and the world.” Oken Tayeng, director of the museum, added: “This is also a recognition of all locals of Arunachal Pradesh who were and are still an integral part of this mission of respecting the memory of others”.

The museum starkly highlights the dangers of flying this route. In his vivid memoirs of the operation, Maj Gen William H Tunner, a US Air Force pilot, remembers navigating his C-46 cargo plane over villages on steep slopes, broad valleys, deep gorges, narrow streams and dark brown rivers.

The flights, often navigated by young and freshly trained pilots, were turbulent. The weather on The Hump, according to Tunner, changed “from minute to minute, from mile to mile”: one end was set in the low, steamy jungles of India; the other in the mile-high plateau of western China.

Heavily loaded transport planes, caught in a downdraft, might quickly descend 5,000ft, then swiftly rise at a similar speed. Tunner writes about a plane flipping onto its back after encountering a downdraft at 25,000ft.

Spring thunderstorms, with howling winds, sleet, and hail, posed the greatest challenge for controlling planes with rudimentary navigation tools. Theodore White, a journalist with Life magazine who flew the route five times for a story, wrote that the pilot of one plane carrying Chinese soldiers with no parachutes decided to crash-land after his plane got iced up.

The co-pilot and the radio operator managed to bail out and land on a “great tropical tree and wandered for 15 days before friendly natives found them”. Local communities in remote villages often rescued and nursed wounded survivors of the crashes back to health. (It was later learnt that the plane had landed safely and no lives had been lost.)

Not surprisingly, the radio was filled with mayday calls. Planes were blown so far off course they crashed into mountains pilots did not even know were within 50 miles, Tunner remembered. One storm alone crashed nine planes, killing 27 crew and passengers. “In these clouds, over the entire route, turbulence would build up of a severity greater than I have seen anywhere in the world, before or since,” he wrote.

Parents of missing airmen held out the hope that their children were still alive. “Where is my son? I’d love the world to know/Has his mission filled and left the earth below?/Is he up there in that fair land, drinking at the fountains, or is he still a wanderer in India’s jungles and mountains?” wondered Pearl Dunaway, the mother of a missing airman, Joseph Dunaway, in a poem in 1945.

The missing airmen are now the stuff of legend. “These Hump men fight the Japanese, the jungle, the mountains and the monsoons all day and all night, every day and every night the year round. The only world they know is planes. They never stop hearing them, flying them, patching them, cursing them. Yet they never get tired of watching the planes go out to China,” recounted White.

The operation was indeed a daredevil feat of aerial logistics following the global war that reached India’s doorstep. “The hills and people of Arunachal Pradesh were drawn into the drama, heroism and tragedies of the World War Two by the Hump operation,” says Mr Tayeng. It’s a story few know.

Source : BBC