Vinay Shukla’s documentary While We Watchedbegins with TV journalist Ravish Kumar walking among the debris of a torn-down floor at the NDTV office. The scene could be a stand-in for Kumar navigating through the remains of India’s TV media.

Being a part of a shrill and populist mediasphere, Kumar has been touted as being amongst the handful voices worth listening to. Shukla and his team followed Kumar between 2017 and 2019, as the channel battled dwindling ad revenues, declining viewership, a revolving door of Kumar’s colleagues, and a hostile takeover set in motion during that period that was completed earlier this year. We see Kumar disillusioned, defeated and bitter. We also see him doting on his daughter, arguing in good faith with abusive trolls and looking distracted.

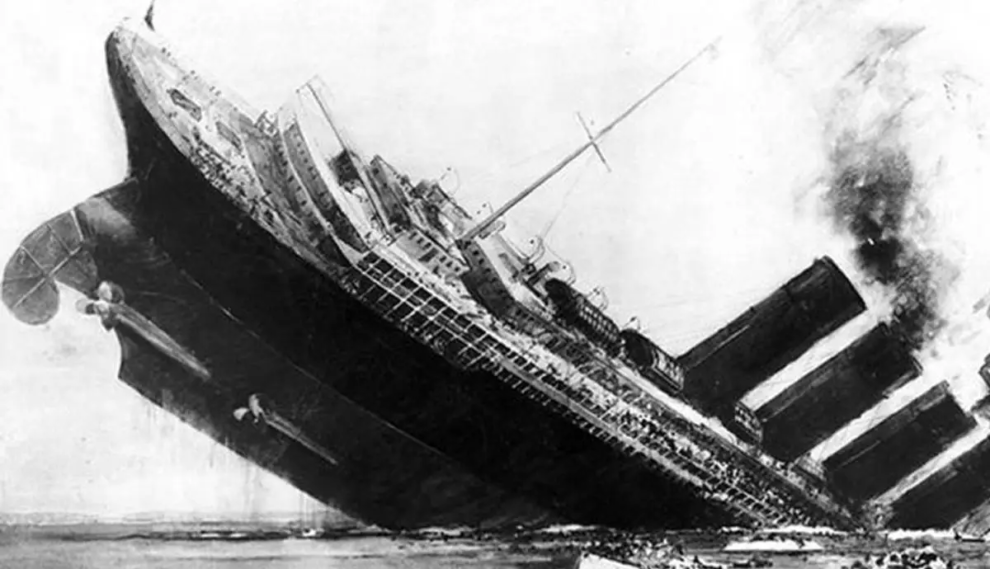

Shukla’s film is a stirring portrait of a time when TV news has exceeded all limits of parody. Shukla has likened the film to the Titanic – where an entire industry is slowly sinking into the abyss right in front of our eyes. To his credit, however, what could have been a more hysterical film is largely meditative and introspective.

The documentary feature had its world premiere at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), its India premiere at the 2023 Jio MAMI Mumbai International Film Festival and played at the recently concluded 2023 Dharamshala International Film Festival, among many other festivals across the globe. The film also recently won the DOC NYC Shortlist Directing Award and Producing Award.

Having been on the radar for over 14 months, Shukla says he’s yet to receive a “term sheet” from a streaming platform or a distributor. But he’s no stranger to these pre-release struggles, given how his earlier film An Insignificant Man(which he co-directed with Khushboo Ranka) also faced a lengthy battle with the censors, before it released theatrically.

In an interview with The Wire, Shukla speaks about finding a narrative by scouring through hundreds of hours of footage and shaping a film that doesn’t merely engage with its echo chamber, and other things. Was there a specific moment when you decided on your film being about India’s rapidly-deteriorating TV media? How did Ravish Kumar become the protagonist?

I remember reading a news article – I think it was a Newslaundry piece in 2018, which had a headline “NDTV liquidates 7.38% stake in subsidiary to pay office rent.” I was caught off guard that NDTV – an institution which was such a regular fixture during my growing up years – is in trouble. So, I remember my first question was – why is this happening? Who is this Ravish guy, berating his audience? And what is really going on in the NDTV offices?

I came across Ravish (Kumar) in a phase where he was very contemplative while being on air. Instead of praising his audiences, which is what prime-time anchors often do, he would criticise his audience, telling them how they weren’t doing enough. He was on TV, and he was asking his audience to stop watching TV. It was highly unusual, and I thought it was a great starting point of inquiry into the lives of those working in TV media.

I like how even in a bleak film like this, you’ve still managed to retain a sense of humour – the scene where Ravish Kumar seems distracted during a celebratory cake being cut in his office, for example – it almost become a metronome for the narrative.

The cake-cutting scenes were my homage to the Godfather films. Usually when there are oranges on screen in the Godfather films, something ominous happens soon after. The cinema student in me always had this in the back of my head that I’d love to do something similar.

I came across a cake cutting on the first day that I was shooting in the NDTV office: you could immediately tell the air was heavy, and someone was leaving in less-than-ideal circumstances. People, who had probably been at this job for 20-25 years, were asked to go search for a new job out of the blue. I understood that what was happening around the cake cutting was poignant. I saw so many cakes being cut, and I somewhere wanted people’s attention back to the crisis within the news industry. Somewhere, we’ve become desensitised.

You’ve often spoken about the film being like that day on the Titanic, where musicians were playing even as the ship was going down. Would that make the cake-cutting the equivalent to those life-boats…

Nice line, I think I’ll start using it as my own! I’ve met cricket journalists and film journalists, who are finding it hard to go against mainstream narratives set by the people in power. Very often, people get obsessed with the politics of this film, which is there, but if you’re looking at building better systems – the conversation is so large. I showed this film to a friend who runs a medical startup – and he said that I had managed to condense the startup life. Everyone keeps telling you you’re bleeding too much cash, someone is poaching your employees, and you’re literally just soldiering on because you believe in something. While We Watched is about the loneliness of being an idealist – people who choose to believe, and persevere on.

Was it hard to find a flaw in Ravish – to make him seem more human than an ideal? Did you manage to crack it?

I don’t think Ravish is an ideal in the film. It starts off with him saying “I want to give up!” It’s not a great way to introduce a ‘hero’. A lot of people in the West, who didn’t know who Ravish was, they asked who this guy was and why he was so negative. I’ve tried to build a portrait of where Ravish is at, vis-a-vis his contemplations about where TV journalism is at. There are scenes, when you see him on stage against a teacher, and people have told me how they’ve interpreted the scene as where Ravish knows to get the people behind him, while the teacher doesn’t.

“Kya aapko aisa Hindustan chahiye tha?” And the audience responds, “Nahi!” He knows how to run the audience. Also, there’s a scene where he gets angry at his producer in the middle of a broadcast. There are moments when people are leaving, it has subtle commentary about Ravish as a person within the film. People looking for a hero in the film will always find one. And similarly with someone who is looking for someone less, will also find them.

Were you ever concerned that the film might not find an audience outside Ravish’s echo chamber? Did you make any specific choices for it?

No. I think my intention was always to make the best film possible, for an audience that you care about. If the film is on solid ground, it’s potent – it will make its way in all directions. I can do certain things as a filmmaker, make certain choices. But if only the choir gets what I want to say then the problem is with my messaging, and not the people. The story has to stand on its legs, if that happens then the message will get across. Which filmmaker wants to limit their audience, yaar? We all want to show our films to as many people as possible.

I make my films with a clear understanding that I want my family and friends to watch and enjoy it. I’m very close to them, and I don’t think we’re very dissimilar. When I speak to them, I’m exercising a certain emotional vocabulary and that’s what I also exercise while making the film. My own family goes and watches each and every film out there, has voted for every major party, and my litmus test is if my family and friends can engage with the film then the audience outside will engage with it too.

Are you hopeful about releasing the film widely in India? How do you plan on doing it?

I’m always hopeful. The film recently just had its India premiere (at MAMI), and I will now approach both theatres and streaming services. I’m in conversation with everyone, they’ve all given me a lot of love for the film, but I don’t have an offer from any platform yet. I’ve met every streamer in town. People are aware of my work, streaming services looking to do non-fiction work – I’m the first person they’ll call. I have many friends there, but I don’t have a term-sheet from any of them.

I’ll also say this, which I tell many others. This entire film distribution set-up via theatres and streaming platforms – we’re a part of it. I don’t want to take pot-shots at streaming services and theatrical distributors, pointing fingers that they are the problem. We need to zoom out and see the problem with the culture at large. The audience also has to pick up some responsibility here.

Some of your colleagues like Payal Kapadia, Rintu+Sushmit weren’t able to release their films in India. What gives you the encouragement to keep going in such times?

Madness. Filmmakers, especially in India, are a crazy bunch! Why do we want to do this? Because we feel like it! There’s no rationale or logic here. Why are you investing 4-5 years into a film that might not get a wide release? You do things because it feels like the right thing to do.

There are a lot many things wrong with the country at the moment. What’s something you think we need to fix in the short-term, and do you see any silver-linings?

On YouTube, there are lots of people – cultural commentators, influencers doing great work. I think YouTube is the punk rock of our era. It’s where a lot of the great journalism is coming from, and I look at it as a source of constant inspiration.

We have to talk about frameworks. I think we often get seduced by the power of one, and I realise I’ve just made a film on Ravish Kumar and NDTV. If we get caught up with one anchor, news channel, or political party, sooner than later they will disappoint us. What are we doing to take care of our journalists – why are they being offered six-month contracts? Why are we paying them so less, and expecting them to be superheroes? The change has to be systemic.

Source: The Wire