Indian opposition leader Rahul Gandhi’s visit to the US has been met with a mixture of excitement, curiosity and scepticism.

The Indian diaspora might not have turned up in thousands like they do for Prime Minister Narendra Modi. But, for a politician who is no longer a member of parliament, nor the leader of the opposition, volunteers of the Indian Overseas Congress – Congress party’s international chapter – managed enough people to fill the audience for Mr Gandhi’s events.

Mr Gandhi is in the US on a three-city tour this week, with stops at the Stanford University in California and the National Press Club in Washington DC.

His visit comes on the heels of an electoral victory over the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in southern Indian state of Karnataka.

The Congress leader is also riding the momentum of the Bharat Jodo Yatra – a 4,000km (2,485 miles)-long “unity march” he led across India over the course of five months – a feat he has referenced at every meeting.

During his visit, Mr Gandhi has taken shots at the Indian government and criticised PM Modi. He has wooed the Indian-American community, praising them for their work ethic and for their success in Silicon Valley.

At Stanford, students lined up to listen to Mr Gandhi speak and take selfies with him. At another diaspora event, people referenced his Bharat Jodo march as they raised calls to unite India.

Sam Pitroda, chairperson of the Indian Overseas Congress, called the march “a turning point” for Mr Gandhi. “There is energy here because of his yatra,” he says.

But why does an Indian politician, who does not have a huge international following, want to woo the diaspora?

Indian-Americans have the highest median income among all immigrant communities in the US and contribute significant funds to American and Indian political parties. With Indian-Americans playing an active role in US politics as voters and candidates, they are considered more than “soft power”.

A 2019 study found that donors from the community gave the most in individual contributions to Democratic candidates compared to other Asian Americans.

Any positive news coverage reported back home also has the potential to “boost electoral prospects” in India, says Milan Vaishnav of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think-tank in Washington.

But projecting a reputation on the upswing will be “a tall task” for Mr Gandhi, says Temple University’s Sanjoy Chakravorty, co-author of The Other One Percent: Indians in America. While Mr Gandhi may intend to cultivate international relevance, “he’s been turned into a bit of a joke in many circles,” Mr Chakravorty says. “So, there is always an attempt at gravitas, to be taken seriously.”

Mr Vaishnav calls Mr Gandhi’s visit “ill-timed”. PM Modi is scheduled to visit the US and attend a state dinner in his honour at The White House on 22 June.

“It’s pretty hard to compete with those optics,” Mr Vaishnav says. “If you’re a foreign politician, it is the highest honour that we have, and direct comparisons will be made.”

Mr Modi’s rockstar-like appeal among the Indian diaspora is “unique”, he says.

As India’s economic power ascends and its alliance with the US grows stronger, political influence of Indian-Americans in the US and the role they play in India’s foreign policy has risen.

Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was one of the first to start engaging with the diaspora in the 2000s.

In 2014, nearly 20,000 Indian-Americans cheered for PM Modi at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

“Is there another world leader who would have the capacity or audacity to sell out Madison Square Garden?” Mr Vaishanv asks. “I can’t think of anyone.”

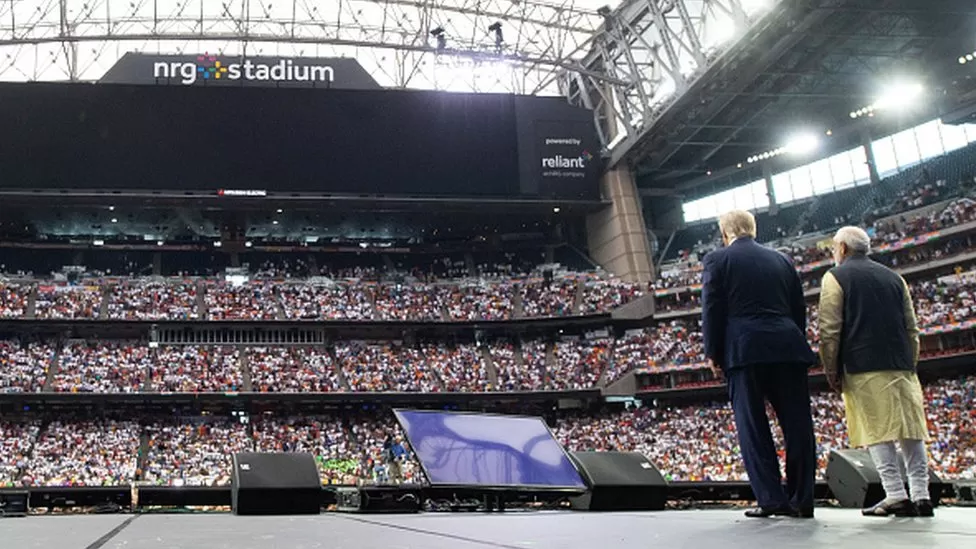

In 2019, 50,000 Indian-Americans arrived at a Houston event to see PM Modi with then US President Donald Trump. It was the largest reception a foreign leader had received in the US, apart from the Pope. Mr Trump called it “exceptional”.

There is no precedent for such large public rallies abroad by Indian leaders, Mr Chakravorty says. “Indian prime ministers have come many times, met high level officials, negotiated trade deals, held talks. But they haven’t done big public events,” he says. “Modi’s style is to go big and be visible.”

Why do Indian-Americans, who can’t vote in India, care about Indian politicians?

The community is known to sustain deep familial, cultural and economic ties with their homeland. For many, personal investments are at stake.

California resident Pooja Lakhia says members of the community have great jobs in the US. “Many might go back or stay here, but a lot of us have investments in India – land, house, stocks,” she says.

Ms Lakhia – a self described “Modi fan” – thinks it’s “important for Indian politicians to engage” with the diaspora but showed no interest in attending a community event hosted by Mr Gandhi.

With high rates of college education, Indian-Americans acknowledge they are beneficiaries of public institutions of higher education in India. The Indian economy, in turn, benefits from its industrious diaspora – a central bank official said the country received $108bn (£86bn) in remittances from overseas Indians last year.

While the community is often criticised for its involvement in domestic politics while leading comfortable lives in the US, the diaspora finds that events with Indian politicians send a very important message to Indians back home that “our hearts are there with them”, says Anu Maitra, a trustee at the University of California, which hosted Mr Gandhi.

“It’s not as if living abroad means you are out,” she says. “You expect us to bail you out of balance of payments problems but not speak up?”

Silicon Valley-based entrepreneur Talat Hasan says many first generation Indian-Americans have a strong connection with the country. “We were raised in the post-independent India with a strong sense of patriotism,” she says.

Many dream of returning to the country to give back what they received from it as shown in the Bollywood film Swades. The film, starring Shah Rukh Khan, shows an Indian-American NASA scientist return to develop his village in India.

Ravi Kuchimanchi, the Indian-American engineer whose life inspired the film, travelled to California this week to hear Mr Gandhi talk.

“He came across as an honest person and he needs to tell non-resident Indians how to help him,” Mr Kuchimanchi said.

The diaspora’s willingness to help India goes “beyond sentimentality,” Anjali Arondekar of University of California. “The big reason is not because we are sending large remittances. [It’s that] Indian youth in the US are looking for a connection with India.”

For Indian politicians, opportunities to interact with the diaspora are also growing.

Stanford University’s Dinsha Mistree, who hosted an event for Me Gandhi, says the “non-partisan” campus has become a stop for prominent Indian leaders when they visit California. Sitting beside Mr Gandhi, he offered an open invitation to PM Modi next.

Source : BBC