Forced to leave her home and job, Budhini Manjhiyain, a tribal woman from the Indian state of Jharkhand, spent her entire life in exile.

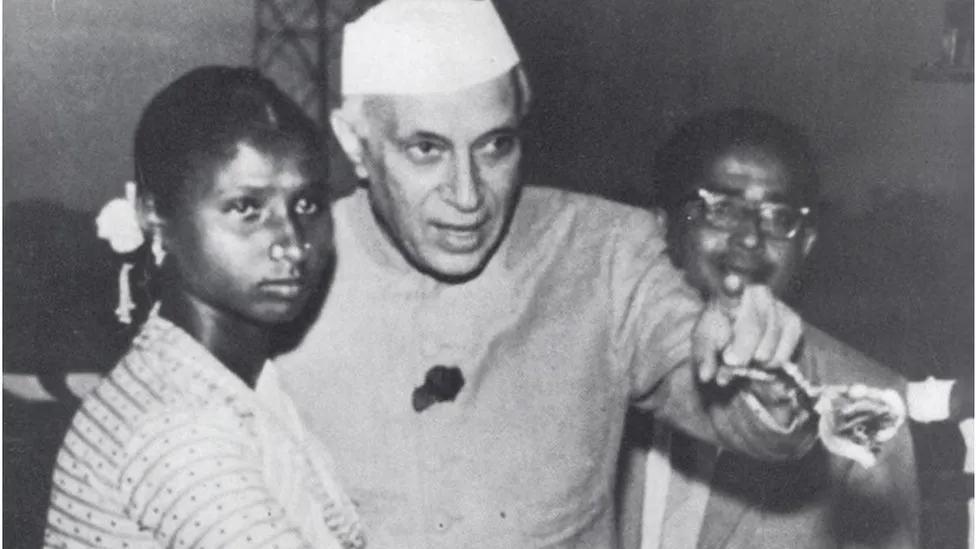

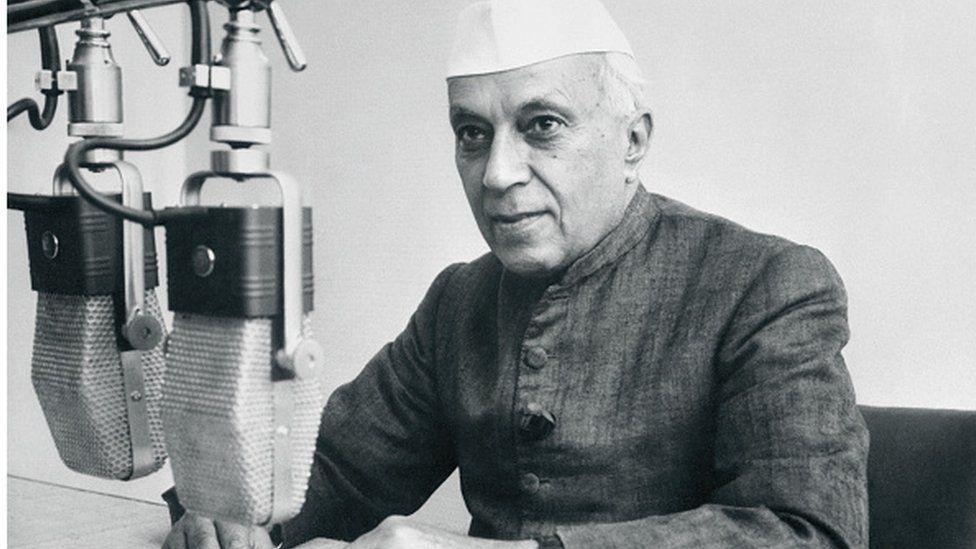

Manjhiyain, who died last month, was just 15 when she was ostracised by her tribe – the Santhals – for garlanding India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru 63 years ago. Under Santhal customs, exchanging garlands is akin to marriage.

Manjhiyain – and the hardships she endured – remained unknown to most, but her death has sparked renewed interest in the woman described by some as “Nehru’s first tribal wife”.

Many in Jharkhand are now demanding a memorial for her, next to an existing statue of Nehru in the village.

Very little is known about Manjhiyain’s early life. Her Wikipedia page is scant, created only after her death. Every once in a while, a newspaper or website would write about her, but the information seems frustratingly incomplete.

In 2012, a leading newspaper wrongly reported that she had died, living her last years in impenetrable obscurity and misery.

It was these inconsistencies that pushed Sarah Joseph, a writer based in the southern state of Kerala who has written a book inspired by Manjhiyain’s life, to find her personally and “bring her back to life”.

Ms Joseph says that when she first met Manjhiyain in 2019, she found it hard to talk to her because they didn’t speak a common language. “Yet, I understood her completely,” she told me.

Manjhiyain grew up in Dhanbad, a small town located in the heart of India’s coal fields in Jharkhand, a lush land of rippled hills where tribespeople make up a quarter of the population.

She was among the thousands of workers who were employed in the ambitious Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) project in the region. This was the country’s first “multipurpose project”, a network of dams, thermal and hydroelectric plants which would lay the foundation for modern India – Nehru once described it as “the noble mansion of free India”.

But building it was equally controversial. Thousands of local people, most of whom were tribespeople, were evicted from their ancestral lands to make way for its construction. Hundreds of villages – including Kabona, where Manjhiyain lived before she was ostracised – were submerged in its aftermath.

In 1959, Nehru announced that he would go to inaugurate one of the dams, called Panchet. To her surprise, the DVC chose Manjhiyain and a colleague to welcome the prime minister.

Then everything went wrong.

At the ceremony, Manjhiyain was asked to garland the prime minister. What she didn’t expect though was that Nehru would playfully garland her back.

He also insisted that the 15-year-old press the button at the dam’s power station to officially launch operations.

That evening, when Manjhiyain returned to the village, she didn’t know it was the last time she was going home.

The village headman summoned her and said that by garlanding Nehru, she had become his bride. He said she had also broken the Santhal code of marrying an outsider and, to atone for her offence, she had to give up everything and leave.

Santhals are known to be a peaceful tribe. They live in small tight-knit communities and follow their own ritualistic codes.

The tribe proscribes marrying outside the community and violators are routinely punished with social ostracism. But activists say the practice is often used as a tool to oppress women.

Tribal men migrate for work all the time but young, unmarried women rarely leave their village – let alone in such difficult circumstances. Those who do, often become the subject of scorn and discrimination.

Manjhiyain knew that if she left, she could never return. She tried to resist and reason with the village head, but the community’s verdict was swift and sure – to them, she had already become an outcast.

“No-one helped her. She got death threats from her own people,” Ms Joseph says.

Helpless, the 15-year-old picked up her things and left.

The dam’s inauguration was hailed as a milestone in modern India’s history.

While Manjhiyain was mostly absent or mentioned in passing, one daily covered “the young Santhal” in some detail, describing her as the first worker “to declare a dam in commission” in India.

It was around this time that she earned the title of “Nehru’s tribal wife”, Ms Joseph says.

The tragedy is that Manjhiyain had no clue about this – she was busy trying to survive what had been the most harrowing few months of her life, enduring ostracism and abject poverty, she adds.

“Everyone was reading about her, but no-one helped. She had nowhere to go.”

Things got worse in 1962 after the Damodar Valley Corporation sacked her, forcing her into daily wage work. The DVC did not give a reason for her termination.

Ironically, the prime minister remained unaware of her suffering. It’s equally ironic how Nehru, one of the foremost exponents of progressiveness and modern thought, came to be associated with this story.

Years passed before a silver lining appeared in Manjhiyain’s life – the exact timeline is not clear – when she met a man called Sudhir Dutta.

Dutta worked at a colliery in the neighbouring West Bengal state, where she now lived. The two fell in love and married.

Ms Joseph says the couple lived in poverty and Manjhiyain tried – unsuccessfully – to get her job back on several occasions.

It was only in 1985 that two journalists, researching her story, approached Rajiv Gandhi, Nehru’s grandson and then prime minister of India, Ms Joseph says.

Finally, after two decades, Manjhiyain got back her job at DVC and worked there until retirement.

“But what was her fault to begin with? That question remains unanswered,” Ms Joseph says.

Manjhiyain personally, though, never looked back – she left behind her traumatic past to live a life of peace.

“What happened to my grandmother was wrong, but during her last moments, she did not complain and was at peace,” her grandson told The Indian Express newspaper after her death.

Ms Joseph says building her statue cannot change the past, but it might help recover her story.

Her struggle is that of thousands of other Indian women, whose dreams are crushed under the weight of patriarchal traditions and intense social pressures.

But she also represents millions of others, who are displaced and forgotten for the sake of modernisation and nation-building, Ms Joseph says.

“She is the symbol of all victims of development. Recovering her is a historical and political need.”

Source : BBC