WASHINGTON — September engagements by President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris in India, Vietnam and Indonesia underscored a trend in international affairs — that countries in the Global South are seeking a more multipolar world in which they can chart their own courses independent of great powers agendas.

This trend is a backdrop to the Biden administration’s view of the power and purpose of American diplomacy at what it sees as a “historic inflection point” — the end of the post-Cold War era and the early days of fierce competition to define what comes next. The result is a policy that is increasingly less ideological and more pragmatic.

Biden attended the G20 summit in New Delhi on Sept. 9-10 and continued with a historic visit to Hanoi to upgrade bilateral ties with Vietnam. On Sept. 6-7, Harris attended the U.S.-ASEAN Summit in Jakarta, Indonesia, with leaders of the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations and the East Asia Summit that brings together ASEAN and its partners.

The themes outlined in these engagements are expected to re-emerge in the Biden administration’s approach in this month’s U.N. General Assembly session in New York.

Global South pushing back

In Jakarta, leaders attending the East Asia Summit saw strong pushback against the geopolitical rivalry among the U.S., China and Russia, summed up in Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s forceful call to ease tensions and avoid conflict.

Widodo’s calls were echoed by leaders of other Southeast Asian countries, from Singapore, which is closely aligned with the U.S., to Vietnam, a communist country seeking diplomatic diversity by upgrading ties with Washington amid Beijing’s increased aggression in the South China Sea.

The region saw much bloodshed during the Cold War. And states such as South Vietnam failed because they chose a side and lost, Brian Eyler, director of the Stimson Center’s Southeast Asia Program, told VOA.

In New Delhi, G20 leaders unanimously welcomed the African Union, the second regional grouping to be part of the bloc after the European Union. The AU’s inclusion bolsters the push to give the Global South a bigger voice on global platforms.

The Global South is getting stronger, and will get stronger in the coming years, said Aparna Pande, director of the Initiative on the Future of India and South Asia, at the Hudson Institute.

It remains to be seen whether the group will have hard power potential, Pande told VOA. But in a world where both the U.S. and China are willing to allow more countries to stay in the middle rather than join the other side, the Global South will have increased diplomatic leverage.

Compromise on Ukraine

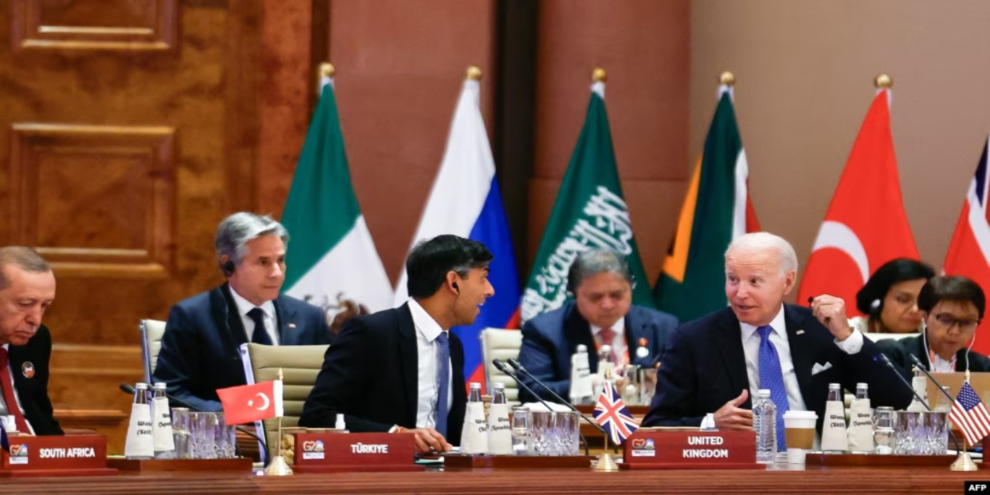

The tricky dance of the great power rivalry was on display as leaders of the 20 largest economies came to a compromise on Ukraine in New Delhi, brokered by summit host India and last year’s chair, Indonesia, both of whom have good relations with Moscow and the West.

This year’s softer G20 communique language avoided direct criticism of Russia, a member of the group, only reiterating that states must refrain from “the threat or use of force to seek territorial acquisition.”

In last year’s Bali summit declaration, by contrast, “most members” condemned “aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine.”

The breakthrough was only possible because the Biden administration sees India as an important counterweight to China and did not want the summit to end without consensus. That would have been a first in the group’s history, embarrassing the Narendra Modi government.

Countering China

The absence of Chinese President Xi Jinping at the summits allowed the Biden administration to project the U.S. as a Pacific power that will counter Chinese aggression, including by bolstering alliances in the region.

Harris quietly did that by inviting Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to chat as leaders were enjoying a gala dinner in Jakarta. She then released a statement underscoring U.S. “opposition to unilateral changes to the status quo in the South China Sea and East China Sea.”

In New Delhi, Biden, Modi and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced a new initiative, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a transnational rail and shipping route spread across two continents to bolster economic integration between Asia, the Persian Gulf countries, Israel and Europe.

The corridor is funded under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), the administration’s alternative to Beijing’s infrastructure investment juggernaut, the Belt and Road Initiative.

More pragmatic foreign policy

Biden campaigned to turn Saudi Arabia into the “pariah that they are” over its human rights abuses and began his administration with a foreign policy that pits “autocracies versus democracies.” But the IMEC deal with Salman, Biden’s growing partnership with an Indian leader criticized for his treatment of minorities, and his meeting with Vietnamese Communist Party Chief Nguyen Phu Trong are more proof that his foreign doctrine has evolved.

“It’s not that the United States is going to Vietnam and opposing communist parties globally,” said Zack Cooper, a senior fellow focusing on U.S. strategy in Asia at the American Enterprise Institute. “We’re dealing with the Communist Party there, where we think our interests are aligned,” he told VOA.

The approach is characterized by Secretary of State Antony Blinken as “diplomatic variable geometry.”

“We start with the problem that we need to solve, and we work back from there — assembling the group of partners that’s the right size and the right shape to address it,” Blinken said in a Wednesday speech at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

“We’re intentional about determining the combination that’s truly fit for purpose,” Blinken added.

Activists have questioned this approach, especially when they believe human rights are treated as an afterthought.

“The White House statement afterwards was pathetic, flagging an ongoing U.S.- Vietnam human rights ‘dialogue’ that conveniently sequesters human rights issues to a symbolic, once-a-year meeting with midlevel officials who talk but don’t get anything concrete done,” Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch, Phil told VOA.

Source : VOA News