A network of middle powers and small states supporting one another. What’s not to like?

From glittering pageantry to a nationwide preponderance of underwhelming quiches, Saturday’s Coronation was a thoroughly British affair. It was, counterintuitively, also the most public celebration of the Commonwealth in most of our lifetimes. The flags of Commonwealth realms adorned the Mall, the names of all 56 member states were sewn intricately into the anointing screen, and Commonwealth leaders took pride of place. For King Charles III, there is no Britain without the Commonwealth.

Charles’ enthusiasm should buoy those who see the bloc’s potential for collective action. Australia’s new King has an agenda that also happens to align closely with foreign policy interests closer to home.

Canberra plays a central role in the modern Commonwealth. Alongside historically strong relationships with Britain, New Zealand, and Canada, it maintains an assertive presence in the South Pacific, warm relations with India, and well-established security partnerships with both Malaysia and Singapore.

There is also clear appetite for deeper engagement with Commonwealth partners. The Government has taken steps to re-engage with the UK via AUKUS, strengthened its ties to India, modernised relationships in the Pacific, and deepened trans-Tasman cooperation.

The Albanese government should now explicitly use the “Commonwealth” label to tie together these disparate foreign policy strands, give a clearer shape to its agenda, and open doors for new and productive partnerships.

Of course, there will be sceptics. Australia has no shortage of multilateral links – why should it focus on the Commonwealth?

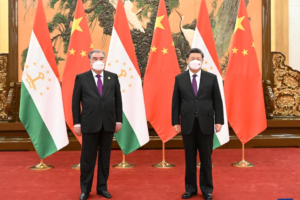

The Commonwealth is the largest international organisation that contains neither the United States nor China.

Albanese and Wong have touted their commitment to “strategic equilibrium”, an international system which emphasises national sovereignty and enables states to work together outside of the bloc politics of the 20th century.

The Commonwealth is the ideal platform for this vision; it’s the largest international organisation that contains neither the United States nor China. If “strategic equilibrium” means anything, it must mean a network of middle powers and small states supporting one another, diversifying their relationships, and shielding one another from the worst excesses of great power politics.

The Commonwealth is stuffed full of modestly sized countries, most of whom share a legal system, compatible constitutions, and the widespread use of the English language, some of whom share deep and beneficial cultural links. It is also home to some of the states which will define global affairs in the coming decades, including India, Bangladesh, Guyana, Nigeria, and Ghana. This is a useful, if not always harmonious, club to be a member of. Within this variable bunch, Australia is a respected leader, able to use its credibility to convene a diverse range of partners and punch well above its weight.

What would a renewed Commonwealth policy look like in practice?

It’s partly a question of emphasis. Where possible, Commonwealth partners should be the first port of call in any given region of the world, and existing multilateral groups should be expanded to include compatible Commonwealth member states. DFAT mandarins should get used to talking and thinking about the Commonwealth.

It’s also a question of expertise – Australia should embark on a campaign of education and institution-building. Flood-defence lessons being learned the hard way in the Pacific would be welcome in the Caribbean, and Australia’s own fire-fighting capabilities would meet with a receptive audience in drought-stricken East Africa. Meanwhile, fast-growing Nigeria would benefit immensely from help in conscientiously developing its mining sector.

Security must also be a pillar. Commonwealth values require robust and active defence. Australia should push to expand AUKUS, including New Zealand in the non-nuclear component, a move that has already been floated. Canada might then be drawn in, and exercises of the Five Powers Defence Arrangements regularised – perhaps these could be used to build defensive capacity amongst the Pacific states. All the while, friendly India must be kept firmly in the loop. In this, Australia is the hub coordinating the spokes, leveraging its international clout and encouraging like-minded states to mutually assure the defence of national sovereignty and self-determination.

The backbone of an Australian policy on the Commonwealth thus emerges as a vast interwoven web of Indo-Pacific democracies, sceptical of China and firmly committed to their national sovereignty. In turn, this web should build robust links with partners elsewhere, particularly in Africa, offering an economic and diplomatic safety net for states who fall foul of the wrath of would-be hegemons. Strategic equilibrium in action.

It is important that this is carried out in the spirit of multilateralism – but a multilateralism that must not rely upon the great American elephant in the room. Washington’s involvement in AUKUS drew the ire of Kiribati, Malaysia, and Solomon Islands, who raised concerns about the Pacific being turned into the staging ground of a reheated Cold War.

A neat side-stepping of this new Great Game is a must if countries outside of the traditional and narrow Western bloc are to be engaged on their own terms. These North-South partnerships are precisely what make the Commonwealth such a powerful group.

A renewed Commonwealth focus could prove to be the most consequential shift in Australian foreign policy since its original pivot away from Britain. Canberra should embrace the opportunity with both hands.

Source: lowyinstitute