On 26 June 1975, the police arrived at a hostel in India’s southern city of Bangalore and arrested Atal Behari Vajpayee, a prominent opposition politician.

The previous evening, prime minister Indira Gandhi had imposed a state of Emergency and plunged the nation into an extraordinary crisis. Elections had been suspended, civil rights curbed, the media gagged and critics and opposition politicians rounded up. Gandhi also banned the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological fountainhead of the later-day Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which rules India today.

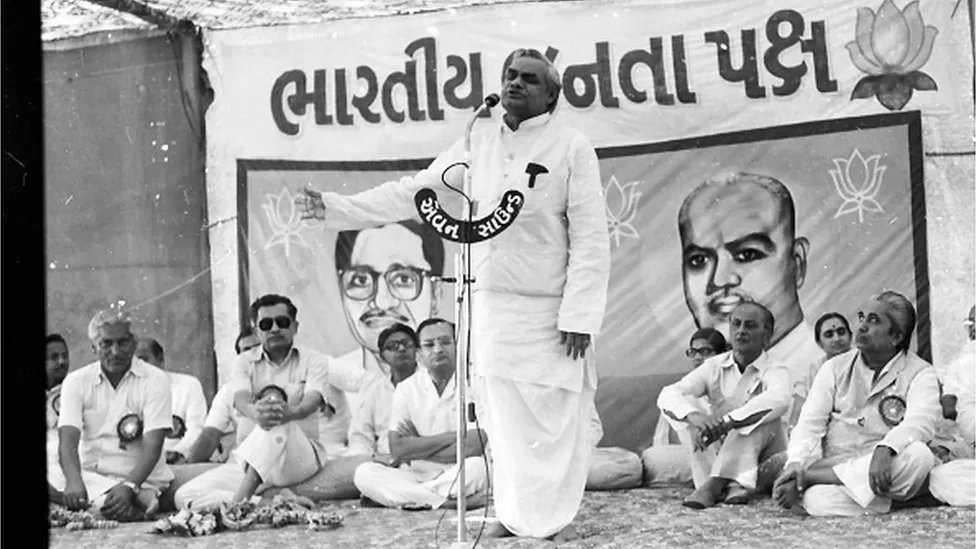

Vajpayee was then a leader of the Jan Sangh, the right-wing forerunner to the BJP, and a member of the RSS. More than two decades later, he had risen to become India’s prime minister – twice briefly in 1996 and 1998, and then a full term, leading a coalition federal government, between 1999 and 2004.

Back in the summer of 1975, Vajpayee was facing arrest. He asked a party worker about the “best jail” in the city, and looked “bored, but sat stoically” in the police station. Finally, he spent a month in prison, writing poetry – naming himself a “kaidi kavirai” or the prisoner poet – playing cards and supervising in the kitchen.

In July, Vajpayee was flown to Delhi in a special plane, after a botched medical diagnosis. In the capital, he spent time, first in hospital recuperating from a surgery and then at home on parole under the watch of the police. By mid-December, Vajpayee appeared to be despondent. “The sun in the evening of my life has decided to set…Words are devoid of meaning…What was music once is now scattered noise,” he wrote in a poem.

A movement distributing clandestine literature and organising civil disobedience – mainly kept alive by RSS pracharaks or full-time apostles – against the Emergency was already fizzling out. Her advisers were pressuring opposition leaders to sign a “surrender document” so they could negotiate with the government. Vajpayee, according to a riveting new biography of the leader by Abhishek Choudhary, was “shocked there was no mass uprising against the Emergency”.

What nobody quite reckoned then was that in a year’s time Vajpayee would end up playing a pivotal role in cobbling together a one-party opposition to the Congress. The Janata Party – a coalition mainly of four centrist and right wing parties (including the Jan Sangh) – would hand down a sensational drubbing in March 1977 elections to Gandhi’s Congress party, its first loss in 30 years after independence. (The prime minister had announced general elections in January and lifted the 20-month Emergency later.)

The Janata Party won 298 of the 542 seats. Most importantly, the Jan Sangh held the foremost position within the coalition, winning 90 seats. Mr Choudhary says Vajpayee could have made the “nominal claim” for the prime minister’s job, but at 52 he was too young for the job. (The 78-year Morarji Desai, a spartan and crusty politician, became the prime minister.) The new cabinet included three Jan Sangh members. Vajpayee took office as foreign minister, promising no “immediate or major changes in the country’s policy”, and an improvement in relations with China.

Vajpayee’s ascendancy was clear during Janata Party’s campaign. The charismatic politician with a flair for oratory was Janata Party’s “biggest crowd-puller” after Jayaprakash Narayan or JP, the 72-year-old leader who had united the opposition forces, writes Mr Choudhary. The media described Vajpayee as the Janata’s “glamour guy”. A campaign poster pronounced him a “pride of the nation”.

In many ways, Mr Choudhary told me, it was Vajpayee who played a “crucial role in mainstreaming Hindu nationalism”. This is in sharp contrast to the popular narrative that solely credits Vajpayee’s fellow traveller and BJP leader LK Advani for catapulting the party to power after spearheading the decades old-movement to construct a temple in the northern city of Ayodhya. “This is an ideologically lazy, self-deceptive analysis that wholly bypasses an earlier trend,” the biographer says.

What people forget, Mr Choudhary says, is that much before the rise of the BJP – from a paltry two seats in the 1984 elections to two back-to-back overwhelming majorities in 2014 and 2019 – its predecessor Jan Sangh, to whom Vajpayee belonged, had proved its credentials as a right-wing political party. At their peak in 1967, the Jan Sangh had some 50 MPs and nearly 300 legislators, he adds.

“Vajpayee was a bridge between two eras in Indian politics – the Congress and the right wing. There would have been no Narendra Modi without Vajpayee,” Mr Choudhary says. When the fractious Janata Party collapsed in 1980, Vajpayee proposed that the Jan Sangh should recast itself into a brand-new mainstream political party and the BJP was born.

Many have described Vajpayee as a “mask” or a moderate in a party of hawks. Mr Choudhary says Vajpayee “could not afford to be hardliner” because he had to work with a coalition of disparate political partners and realised that compromise was the key to politics. “But the early Vajpayee, before he became an MP, was hardline,” he says.

Vajpayee was born in Gwalior to a teacher father and a homemaker mother at a time when two major pro-Hindu groups, the Hindu Mahasabha and Arya Samaj were already espousing the idea of Hindu unity. His earliest poems, Mr Choudhary writes, “speak of the intense rage and victimhood Atal felt; that he had come to have a sharp, if also narrow and confused, sense of India’s history and geography, and the need for its revival; and a sense of his own place in the wider world”.

Vajpayee had joined the RSS – formed in 1925 – during his college years. He gave weekly lectures, dreamt of becoming a journalist and wrote a polemic of the history of Islam in India. He edited four right-wing publications, including Panchjanya, the RSS mouthpieces, where he wrote on cow protection, Hindu personal law, India’s relation with the world and Hinduism. He betrayed a prudish streak when he found the songs in Barsaat (Rain), a popular Bollywood film, “dirty and vulgar”, and implored the government to stop children from watching films.

Decades later, Vajpayee appeared to have evolved into a pragmatist. When he was helping the Janata Party cobble together its campaign, the local media praised him for a “degree of moderation, suavity and capacity to grasp issues and reconcile differences”.

One thing is clear, Mr Choudhary says. Throughout his six-decade-long career Vajpayee, who died in 2018, aged 93, remained the “most enigmatic Indian politician of recent times”.

Source : BBC